It is an honor to host my friend, Tracy Barrett, today. I got to know Tracy when we both served on the faculty of the Highlights Foundation Historical Novel Workshop and thoroughly enjoyed her book, Dark of the Moon-- and as a newly retired professor of Italian, she is a fount of knowledge about all things Italia. Please welcome Tracy!

Say you know a teenage girl whose widowed father marries a woman with

two daughters. The girl and her father move in with the stepfamily. If the girl

told you that she had to do all the work and that her stepmother was mean to

her and her stepsisters were ugly and bossy, wouldn’t you tell her that

stepfamilies take some adjustment, and wouldn’t you suspect that maybe there’s

another side to the story?

So why do we take Cinderella’s word that she’s so persecuted?

This was the spark for my novel The

Stepsister’s Tale, to be released in July by Harlequin Teen. Jane, the

older of Cinderella’s stepsisters, tells of living in grinding poverty with a

mother who is in denial that they are no longer the wealthy, high-living family

of her girlhood. Jane and her sister do all the work, and when the beautiful

and spoiled Isabella reacts with indignation at the suggestion that she pitch

in, conflict erupts.

When my children were little and an argument broke out between them, I

discovered that almost always the facts weren’t under dispute: they agreed that

he pushed her, for example. But what differed was the motivation: “He was

trying to knock me down” vs. “It was an accident.” Each was (usually) convinced

that her or his interpretation of the motives was accurate.

What makes fairy tales so ripe for retelling is that almost always, the

villain—such as Cinderella’s stepsisters—is evil for no apparent reason.

There’s no argument over whether the stepsisters force Cinderella to work, but

Cinderella is sure that her stepsisters are bullying her while Jane is equally

convinced that they’ll starve if everyone doesn’t work hard.

And fairy tales rarely show character growth: Cinderella starts out

good and sweet and beautiful, and at the end she’s good and sweet and beautiful.

The stepsisters start out as selfish bullies, and at the end they’re selfish

bullies. The author of a retelling is tasked with not only figuring out why

these fairy-tale people act they way they do but also showing their

development.

No one is a villain (or a sidekick or a mentor) in her or his own

story, and in my recent work I’ve enjoyed exploring other secondary characters

from well-known stories.

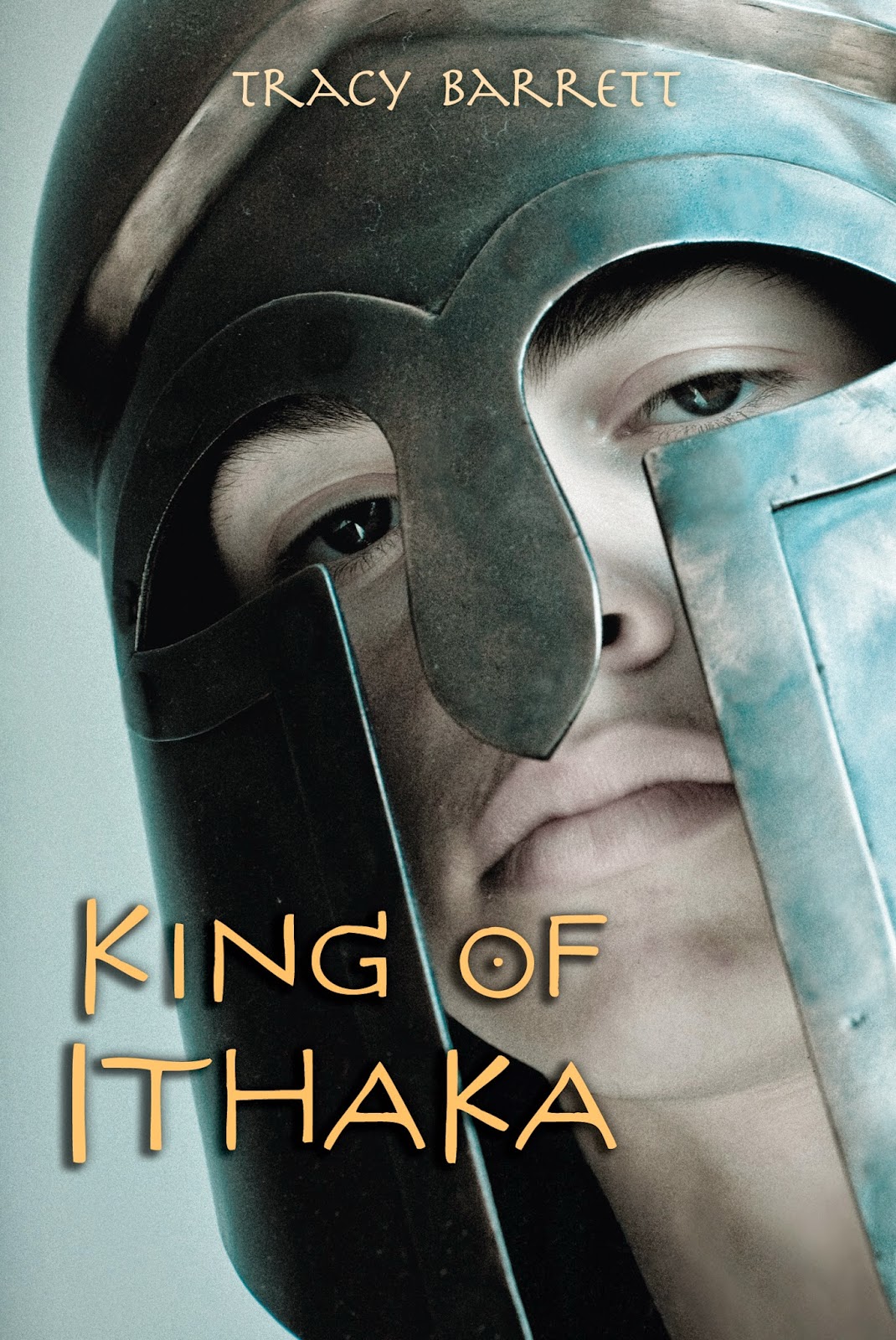

King of Ithaka

tells part of Homer’s Odyssey from

the point of view of Telemachos (Odysseus’ teenage son), and Dark of the Moon is the tale of the

minotaur as told by the minotaur’s sister, Ariadne, and his killer, Theseus.

Of

course I hope that my readers enjoy these books for their own sake, but I also

hope that by reading my novels. they’ll see another layer to the familiar works

that inspired me.

Tracy

Barrett is the author of twenty

books for young readers and one book for adults. Her first young-adult novel, Anna

of Byzantium, received numerous awards and honors, including being named a Booklist

Editors’ Choice book, a Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books Blue

Ribbon Book, and an ALA Quick Pick. She is also the author of the acclaimed YA

historical novels King of Ithaka and Dark of the Moon as well as the popular

middle-grade series The Sherlock Files. You can visit her online and follow her on Twitter.

Thank you for inviting me to guest post, Kirby!

ReplyDeleteAh, nice to see you together here. The new book sounds terrific, Tracy. I'll be looking for it.

ReplyDelete